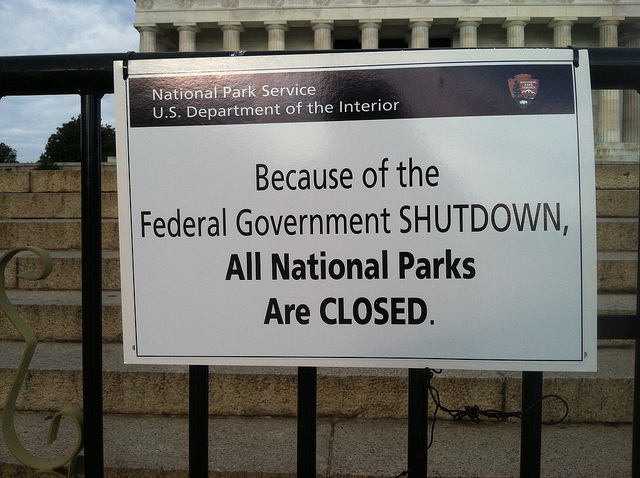

If you’ve been planning a trip to visit a ghost town this winter, you might want to think about postponing your adventure. Not only because it’s cold/snowy/rainy but because of the federal government shutdown last month.

All US National Parks are closed and subsequently our beloved ghost town tourist attractions. Not to mention the possibility of a delayed tax refund (nooooo!), and of course, our friends and family who have been furloughed for two weeks now.

The National Parks are still open to the public but staff have either been reduced or not present at all. School field trips, vacations, recreational activities, and wildlife have also been affected. This affects all of us.

Here is a list of which ghost towns have been affected by the shutdown. If you do travel to any of these, proceed with caution.

Ghost towns affected by the shutdown

1. BALLARAT, CALIFORNIA - DEATH VALLEY NATIONAL PARK

Photo courtesy of geoff dude on flickr

Ballarat came into being in 1897 with many gold strikes in the Panamint Mountains. The Radcliffe mine alone produced 15,000 tons of gold ore from 1898-1903. The town was named after a famous Australian gold camp and was home to 400 people in 1898.

Several legendary Death Valley figures lived in town. Ballarat is now privately owned and contains the ruins of several adobe buildings.

The townsite is located off the Panamint Valley road west of Death Valley proper.

2. Chloride City, California - Death Valley National Park

Photo courtesy of Ken Lund on flickr

Chloride City became a town in 1905 when the Bullfrog strike brought people into the area to re-work old mining claims. It became a ghost town the following year.

There are numerous adits and dumps in the area and one grave of a James McKay, of whom nothing is known. In addition, there are remains of 3 stamp mills.

It is located off a four wheel drive road 3.5 miles east of Hell’s Gate or off the dirt road 7 miles further east at the Park boundary. Turn right after the cattle guard.

3. Golden Crown Mine, California - Yosemite National Park

Photo courtesy of the National Park Service

As early as 1860, prospectors explored Mono Pass in search of gold and silver deposits. Here, among the glacially carved granite and craggy peaks of the Sierra crest, these hardy men discovered silver deposits and went to work in hopes of fortune.

The Golden Crown Mine was established in 1879 by Orlando Fuller during the Tioga silver boom that also produced Bennettville and the Great Sierra Mine near Tioga Pass. Significant wealth was predicted, but around 1890, the mines were abandoned.

Although the period of active mining in the areas of Tioga Pass and Mono Pass was brief, a few good examples of mining structures remain. Five log cabins mark the location of the Golden Crown and Ella Bloss mines.

The Golden Crown Mine is located at Mono Pass, on the boundary of Yosemite National Park at 11,000 ft elevation.

4. Johnson Lake Mine, Nevada - Great Basin National Park

Photo courtesy of the National Park Service

The lake and mine are named for Alfred Johnson, who filed a mining claim in Snake Creek Canyon in 1909. A rancher who also wished to exploit the location opposed him in court, but Johnson prevailed.

Tungsten was discovered in the area in 1912 by John D. Tilford. Tilford set up the Bonita Mine, while Johnson set up the Johnson Lake Mine in 1912. The mine was finally closed when a snowslide destroyed the aerial tram terminal after 1935.

5. Keys Ranch, California - Joshua Tree National Park

Photo courtesy of Joshua Tree National Park

Keys Ranch offers a glimpse into the scrappy, extraordinary lives of early Joshua Tree settlers.

In the high desert, rugged individuals tried their luck at cattle ranching, mining, and homesteading, but few were able to succeed. Bill and Frances Keys were exceptional—not only surviving, but thriving in the desert for 60 years while they raised their family in this remote location.

The ranch house, school house, store and workshop still stand; the orchard has been replanted; and the grounds are full of cars, trucks, mining equipment, and spare parts that complete the Keys Ranch story.

Today, the ranch is listed as a National Historic District, but needs an investment of preservation work to persist into the future.

6. Leadfield, California - Death Valley National Park

Photo courtesy of James Marvin Phelps on flickr

Copper and lead claims had been filed in the Leadfield area as early as 1905 but it wasn’t until 1926 that the area was heavily mined.

In February of that year, Charles C. Julian, a flamboyant California promoter, became president of the town’s leading mining company, the Western Lead Mines. Julian’s promotions were responsible for bringing great numbers of people into the area and in April, 1926 the town was laid out with 1749 lots.

The financial downfall of Charles Julian and the playing out of lead in one of the main mines, led to the end of the town. The area is scattered with mines, dumps, tunnels and prospect holes. There are remains of wood and tin buildings, a dugout and cement foundations of the mill.

The town is located on the Titus Canyon road. This is a one way high clearance unpaved road that sometimes requires 4-wheel drive.

7. Panamint City, California - Death Valley National Park

Photo courtesy of James Houser on flickr

Panamint City was called the toughest, rawest, most hard-boiled little hellhole that ever passed for a civilized town. Its founders were outlaws who, while hiding from the law in the Panamint Mountains, found silver in Surprise Canyon and gave up their life of crime.

In 1874 the town was at the height of its boom with a population of 2,000 citizens. By the fall of 1875 the boom was over, and in 1876 a flash flood destroyed most of the town. The chimney of the smelter is the most prominent remnant of the town’s heyday.

The site of Panamint City is accessible via a 5 mile hike from Chris Wicht’s Camp, which is located 6 miles northeast of the ghost town of Ballarat. Mining in the area continued on a sporadic basis up until recent times.

The ruins of old Panamint City were added to Death Valley National Park in October of 1994.

8. Rush, Arkansas - Buffalo River National Park

Photo courtesy of Dave Thomas on flickr

The best known and most prolific zinc mining region of north Arkansas for many years was the Rush Creek mining district of Marion County.

Its history began when John Wolfer—an early prospector along the Buffalo River—discovered a large deposit of zinc on the creek in southern Marion County. George Chase purchased Wolfer’s claim and established the Morning Star Mining Company, which eventually became one of the largest producers of zinc in Arkansas.

One day a miner at the Morning Star Mine extracted a single mass of pure smithsonite (zinc carbonate) weighing 12,750 pounds.

The miners originally thought that they were mining silver. They soon discovered that the “silver” that they were mining was not actually silver; it was zinc. Two to five thousand people lived in Rush Creek during the boom period, during World War I.

9. Ryolite, Nevada - Death Valley National Park

Photo courtesy of Preconscious Eye on flickr

Ryolite’s birth was brought about by Shorty Harris and E. L. Cross, who were prospecting in the area in 1904. They found quartz all over a hill, and as Shorty describes it “… the quartz was just full of free gold… it was the original bullfrog rock… this banner is a crackerjack” declared Shorty! “The district is going to be the banner camp of Nevada. I say so once and I’ll say it again.”

At that time there was only one other person in the whole area: Old Man Beatty who lived in a ranch with his family five miles away. Soon the rush was on and several camps were set up including Bullfrog, the Amargosa and a settlement between them called Jumpertown.

A townsite was laid out nearby and given the name Rhyolite from the silica-rich volcanic rock in the area.

10. Skidoo Stamp Mill, California - Death Valley National Park

Photo courtesy of the United States Geological Survey

Skidoo was founded in 1906 when two prospectors, on their way to the Harrisburg strike, found gold.

The town reached a population of 700 and became famous as the site of the only hanging to take place in Death Valley. It occurred when Hootch Simpson, a saloon owner who had fallen on hard times, tried to rob the bank, was foiled in the attempt, and later went back and killed the owner of the store in which the bank was located.

During the night the townspeople hanged Hootch. According to legend, he was hanged twice. The second hanging was to accommodate news photographers who missed the first hanging. No one was ever arrested for the hanging.

Skidoo is located off the Wildrose road on an unpaved high-clearance road not recommended for automobiles. Nothing remains of the actual townsite.

11. Whiskeytown, California - Whiskeytown National Recreation Area

Photo courtesy of Wayne Hsieh on flickr

Whiskeytown was one of Shasta County’s first gold mining settlements during the California Gold Rush of 1849, though at the time it was called Whiskey Creek Diggings.

There are two different stories for how the settlement got its name: The first states that a barrel of whiskey fell from a pack mule and into the creek that ran by Whiskeytown; the second attributes the name to the legend that miners at Whiskeytown could drink a barrel of the hard liquor a day.

The area became known as a good place to mine for gold. The Redding Record Searchlight reports miners averaged $50 in gold per day, and in 1851 a 56-ounce gold nugget was found.

The first white woman arrived in town in 1852, and by 1855, about 1,000 gold miners lived in Whiskeytown. The post office was opened in 1856, but the federal government didn’t allow the Whiskeytown name to be attached to it because it was considered inappropriate.

Finally, in 1952, the federal government agreed to name the post office after the town.

What you can do to help

Unfortunately, conditions are unsanitary so I advise those who do visit, not to use the restrooms (if not closed). Trash has been strewn about. It’s amazing how much we take for granted the small (and big!) contributions those working in the parks provide to its visitors.

My advice to you: be courteous, respectful, and try to leave the park better than how you found it. Do your best, at least. If you can, volunteer at a park to make up for the services that have been cut.

If I missed any ghost towns affected by the recent government shutdown, please comment below. What would you do to help? What are your thoughts on how this affections our National Park system?